Segregated Cincinnati: Why 1 in 3 people live in predominantly Black or white neighborhoods

Segregated Cincinnati:

Why 1 in 3 people live in predominantly Black or white neighborhoods

The economic and social forces that drive segregation are complex. But a history of discriminatory housing practices helped shape city neighborhoods.

Dan Horn, Cincinnati Enquirer

Published 9:19 PM EST Feb. 23, 2022 Updated 9:33 PM EST Feb. 23, 2022

Download the full article (PDF)

View background photo collage of the Ellis Family.

When Wendy Ellis’s grandparents decided to move from their home in Avondale in 1966, her grandfather knew he couldn't do the house hunting.

The problem wasn’t his qualifications as a homebuyer. Ellis' grandfather, Ralph Ellis, was a World War II veteran, a lawyer and an insurance company executive. He was, at least on paper, a real estate agent’s dream.

But Ralph Ellis was Black. His wife was white. And Cincinnati was segregated.

If the Ellis family wanted housing options beyond neighborhoods like Avondale, where Black residents had found some success buying homes, Ralph Ellis would need to leave the search to his wife, Germaine.

She was the one who would meet with agents, who would tour homes, who would inquire about loans.

“She was the face,” said Wendy Ellis, who learned about the housing search from her grandparents decades later. “They had plenty of reasons to believe that it was necessary.”

Cincinnati is less segregated now than when the late Ralph and Germaine Ellis began house hunting in the 1960s. But their experience six decades ago is a small part of the history that explains why segregation persists in the city today.

An Enquirer analysis of U.S. Census data found that while Cincinnati’s population is now divided almost evenly between white and minority residents, the distribution of that population tells a more complicated story: Almost 1 in 3 city residents live in neighborhoods that are at least 75% white or Black.

The city’s most segregated neighborhoods include Mount Lookout and Hyde Park, where more than 85% of the population is white, and Bond Hill and South Cumminsville, where more than 85% is Black.

Other large American cities follow a similar pattern: Zoom out, and the population looks diverse. Zoom in, and it looks very different.

“Cincinnati isn’t an outlier,” said Ellis, who now leads the Center for Community Resilience at George Washington University and recently produced a documentary about race and inequity in Cincinnati. “It’s actually a microcosm.”

How a city becomes segregated is complicated. Economics, personal choice and the vagaries of the housing market all play a part in determining why people live where they live and why communities look the way they do.

"Whites did everything they could to stop Black people from moving into what they considered white neighborhoods.”

Fritz Casey-Leininger, a retired University of Cincinnati history professor

But history matters, too. In Cincinnati, as in most large cities, the segregation of today is rooted in almost two centuries of practices and policies that were designed, often intentionally, to keep Black people out of white neighborhoods.

Discriminatory lending practices, unscrupulous real estate agents and zoning laws that limited housing options all stood in the way of minority homebuyers.

Ralph and Germaine Ellis knew this in the 1960s, Ellis said of her grandparents, and Black families in Cincinnati and many other cities still live with the consequences.

Options 'limited' for Black homebuyers

Ralph and Germaine Ellis understood the challenges they’d face in their search for a home because they understood America in the mid-20th century.

A sheriff’s deputy once gave them until nightfall to leave an Indiana town for that reason, Ellis said, and her grandmother would lose two jobs at bakeries after her bosses found out she was married to a Black man.

By the time the young couple moved to Cincinnati in 1949, they knew better than most the role segregation played in American life, from schools to pools to water fountains.

Housing was no exception.

Just two decades before the Ellis family came to Cincinnati, the city’s Real Estate Board made discrimination a job requirement for its agents, ordering them in the 1920s to prevent Black people from following white people to the city’s more suburban neighborhoods.

“No agent shall rent or sell property to colored people in an established white section or neighborhood,” the order said. “This inhibition shall be particularly applicable to the hilltops and suburban community.”

In the 1930s, the Federal Housing Administration didn’t use such openly racist language, but an FHA practice that became known as “redlining” had the similar effect of perpetuating segregation by declaring Black neighborhoods high lending risks.

The practice went on for years, concentrating Black residents in a handful of neighborhoods because they couldn’t get loans to move anywhere else.

Even when Black homebuyers in Cincinnati managed to overcome such institutional barriers, they often met resistance.

In 1944, a white mob forced a Black mother and her children to flee a Mount Adams home by hurling stones through the windows. And in 1947, a homeowners association in Evanston vowed that if a Black person made an offer on a house, it would swoop in, buy the house and resell it to a more “desirable” buyer.

“The places that (Black people) could move to were extremely limited,” said Fritz Casey-Leininger, a retired University of Cincinnati history professor who has studied housing and segregation in the city. “Whites did everything they could to stop Black people from moving into what they considered white neighborhoods.”

An integrated city becomes segregated

It wasn’t always so.

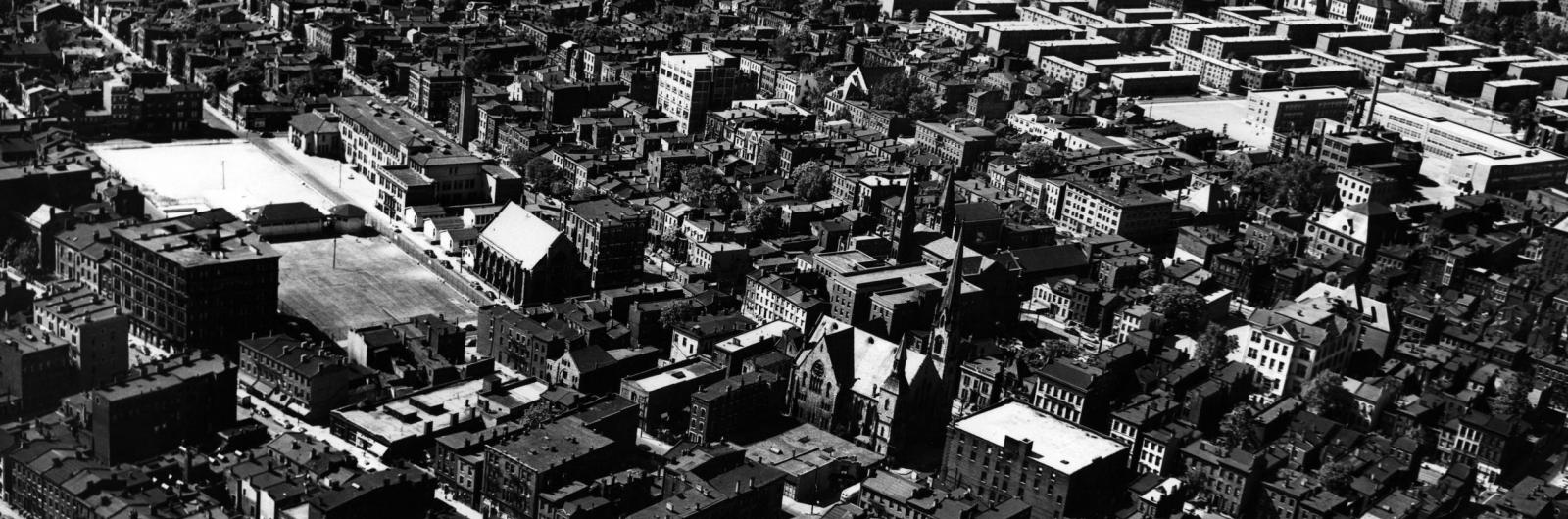

A century before the Ellis family began its search for a new home, Cincinnati was, in many ways, an integrated city. In the 1850s, most of the city’s 115,000 residents, including its 3,200 Black residents, were packed into a six-square-mile area along the riverfront.

Black people and white people had little choice in the matter. Both needed to live close to their warehouse and factory jobs, which meant they also had to live close to one another.

“It was a walking city,” said Henry Louis Taylor Jr., a University of Buffalo historian and professor of urban and regional planning who has studied housing in Cincinnati. “Blacks were living in their residential clusters, but their clusters were embedded in the wider communities.”

That began to change in the 1870s as Cincinnati’s streetcars and inclines made it possible for people to live miles from their workplaces. Soon, those with the means to leave the crowded and polluted riverfront headed for the hills, settling in places such as Price Hill, Mount Auburn and Clifton.

Almost everyone who could afford to go in that first wave was white, leaving behind both poor white and Black people. But by the 1920s, the city’s growing Black population was increasingly on its own, squeezed into densely populated ghettos in the West End.

With few exceptions, living conditions were poor. The Better Housing League in 1923 found 94 Black men, women and children living in a single 12-room tenement on George Street.

“You could not produce a prize hog to show at the fair under conditions that you allow Negroes to live in this city,” said public health pioneer Haven Emerson, during a visit that year to the West End. “Pigs and chickens would die in them for lack of light, cleanliness and air.”

Overtly racist policies weren’t the only reason Black residents struggled to find housing beyond the West End. Structural barriers, such as restrictive zoning laws, often had the same effect.

Alfred Bettman, an influential Cincinnati city planner, led the charge for zoning laws that not only kept industrial sites out of residential neighborhoods but also apartments and multifamily homes that were affordable to working-class Black and white residents.

He described multifamily housing as “disorderly, noisy, slovenly, blighted and slumlike,” and in 1926 he defended restrictive zoning practices before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Taylor said Bettman’s arguments were about class and economics, rather than race, but the zoning policies he advocated were a kind of “nonracist racism.”

“It becomes the tool by which they’re able to construct these highly segregated cities,” Taylor said. “I won’t get into whether they did it intentionally or unintentionally, but it’s clear they were creating the kind of community that Black people couldn’t afford to live in.”

Over time, the city’s zoning policies helped create a housing crunch in Cincinnati, particularly for poor Black people. By 1943, there was roughly 10 times more housing available in white areas of the city than in Black areas.

"I won’t get into whether they did it intentionally or unintentionally, but it’s clear they were creating the kind of community that Black people couldn’t afford to live in.”

Henry Louis Taylor Jr., University of Buffalo, a scholar of urban history.

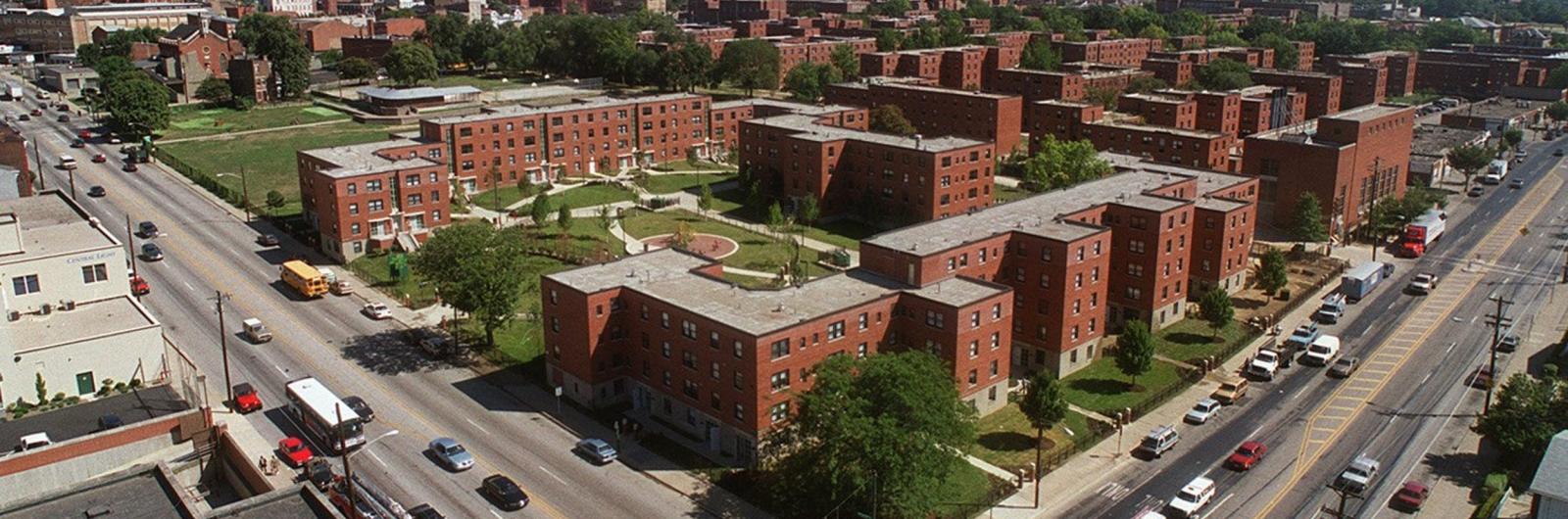

To address the problem, the city began building public housing projects in the 1930s and 1940s. But those projects only deepened the city’s racial divide. Most were built in neighborhoods that already had large Black populations, such as the West End.

And like the city around them, the new housing projects almost always were segregated.

'A colored man's dream'

For Ralph and Germaine Ellis, Avondale was one of the few neighborhoods where they could realistically expect to find housing when they moved to Cincinnati in 1949.

The neighborhood, once predominantly white, was in transition. An enclave of middle-class Black people had settled there in the 1940s and expanded as Black families from the West End began to move north.

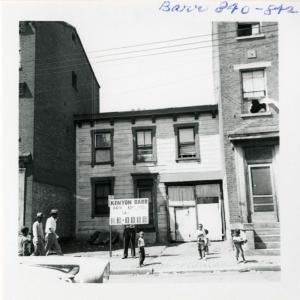

The influx of new Black residents accelerated in the 1950s after city officials razed the Kenyon-Barr district in the West End to make room for highways and businesses, forcing out some 10,000 Black families.

As the Black population grew, Ellis said, investment in Avondale declined and real estate speculators moved in, persuading white residents to sell their property cheaply out of fear that more Black neighbors would mean lower home values.

A 2008 study written by Casey-Leininger, the UC history professor, found evidence that some real estate agents in Avondale went door-to-door in the 1950s, warning white residents to sell. While it’s unclear how much “blockbusting,” as the practice was known, happened in Avondale, a growing number of white homeowners did begin to leave.

The Ellis family began to think about leaving, too. Unlike their white neighbors, however, they knew their options would be limited if Ralph was involved in the housing search.

They were reminded of why almost every day.

Real estate ads in 1950s newspapers made no secret of the city’s racial divide, listing homes in some neighborhoods as “unrestricted,” meaning they were open to Black homebuyers, and labeling other available homes as “for colored buyers” or as a “colored man’s dream.”

There also were more personal reminders of the kind of discrimination the Ellis family would face while looking for a new home.

Ellis said the parish priest once told her grandmother, a devout Catholic, that her sons could not serve as altar boys because they were Black. And when her sons came into the bakery where she worked, Germaine gave them strict instructions: They could not acknowledge her as their mother, or she’d risk losing another job.

It only made sense, Ellis said, to take similar precautions when house hunting. Her grandmother would go alone, with no children and no husband.

The search for a new home ended when the couple decided to move out of Cincinnati, to Madeira, a predominantly white suburb.

“They were able to buy a house without the Realtor ever knowing he was selling to a Black man,” Ellis said.

The consequences of lost opportunity

Change came slowly to Cincinnati and the rest of the country in the years after the Ellis family moved.

The Fair Housing Act in 1968 barred discrimination based on race while lawsuits against lenders and real estate firms in the 1970s and 1980s challenged some discriminatory practices.

But segregation and its consequences have endured, said Eric Jackson, a history professor at Northern Kentucky University and co-author of “Cincinnati’s Underground Railroad.” He said generations of Black families that had the ability to own real estate, grow wealth and improve their lot in life never got the chance because of barriers to homeownership.

Even if some of those barriers have since come down, Jackson said, the damage has been done.

“There’s no quick fix,” he said.

Some of that damage remains visible today. Among Cincinnati neighborhoods that are at least 75% white, all but one has a poverty rate lower than the city average. Among those that are at least 75% Black, all but one has a poverty rate higher than the city average.

That disparity isn't unique to Cincinnati, and neither is the difference in home values between Black and white neighborhoods. A 2018 Brookings report found that homes in predominantly Black neighborhoods are worth 23% less than those of similar quality and with similar amenities in predominantly white neighborhoods. The report also found that factors such as crime and the quality of schools explained only about half of the undervaluation of Black homes.

When Ellis returned to her hometown to work on her documentary, “Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation: Cincinnati,” she visited and studied many of the neighborhoods she knew while growing up, including Avondale, where her grandparents once lived.

Half the people in Avondale today live in poverty. Almost 1 in 5 lack health insurance, 1 in 4 don’t have a high school diploma and renters outnumber homeowners 3 to 1.

With a Black population of just under 80%, it’s also one of the city’s most segregated neighborhoods.

Ellis said if anyone wants to know why her grandparents’ old neighborhood is struggling, they should learn more about Cincinnati’s history. She’s confident they’ll find the answers there.

“We can’t begin to solve these gnarly problems,” she said, “if we really aren’t truthful with ourselves about the source.”

About this story: The Enquirer produced this story as part of its Neighborhood Report Card project, an online database that allows readers to learn more about Cincinnati's neighborhoods. Data for this story was drawn from an Enquirer analysis of the 2020 U.S. Census, the 2019 American Community Survey and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Historical sources include The Enquirer, Ohio History Central, Justia U.S. Supreme Court Center, BlackPast, Cincinnati Blacks and the Irony of Low-Income Housing Reform, 1900-1950 (Robert A. Fairbanks), The Black Residential Experience and Community Formation in Antebellum Cincinnati (Henry Louis Taylor, Jr.), Going Home: The Struggle for Fair Housing in Cincinnati, 1900-2007 (Charles F. Casey-Leininger), the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, Euclid’s Historical Imagery (Richard H. Chused) and Lost Cincinnati (Jeff Suess).